- Open Today: 10.00–18.00

- Ticket

- Shop

- Membership

- TR EN

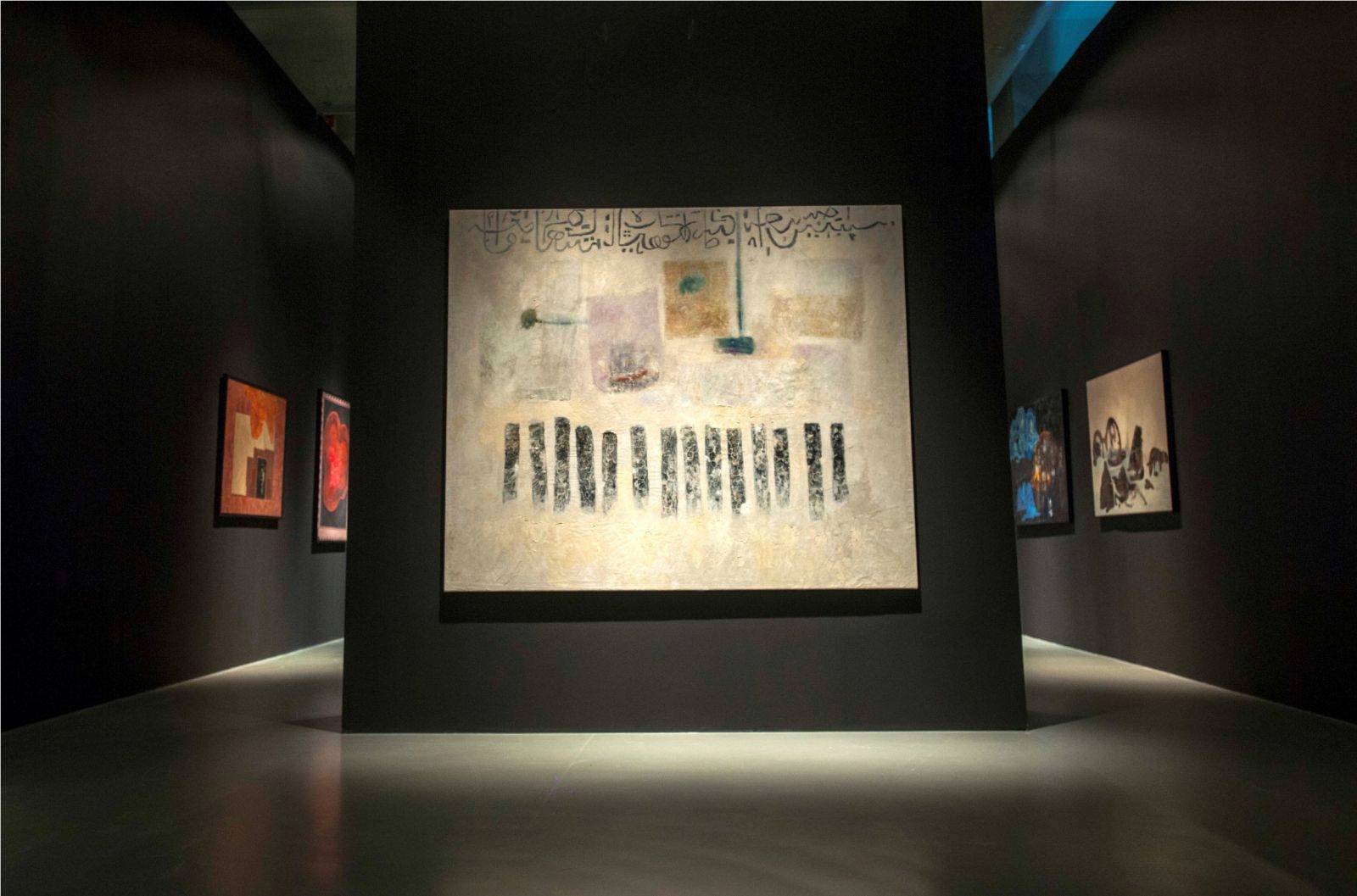

Erol Akyavaş - Retrospective

Istanbul Modern presents a selection of the artist’s oeuvre spanning half a century

Istanbul Modern presents, with its new exhibition titled Erol Akyavaş - Retrospective, a comprehensive selection of the artist’s oeuvre spanning half a century from the 1950s to the late 1990s.

The exhibition that will take place at the Istanbul Modern Temporary Exhibition Hall under the patronage of Ilona Akyavaş and with the support of Finansbank from 29 May to 25 August 2013 features a selection of 290 works. The exhibition brings together in great diversity the unique synthesis Erol Akyavaş developed between the art and cultural worlds of the East and the West, his perspectival and architectural arrangements on the canvas in their transformation over time, his explorations of the subconscious that centred on the human figure, and the encounters he sought with the various cultures of the world.

Born in 1932 in Istanbul, Erol Akyavaş studied painting at the Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu Studio at the Fine Arts Academy as a guest student, and took part in the exhibitions of this studio. He attended summer semester studies at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. He worked with André Lhote and Fernand Léger in Paris. In 1954 he went to the United States of America to study aesthetics and philosophy of art. From 1954 to 1960, he studied architecture with Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology, in Chicago, USA. He also worked as a photographer for a period of time; however, neither photography nor architecture provided Akyavaş with the artistic satisfaction he sought. He returned to painting and until his death in 1999, he produced countless images, and meanings with a style, which went beyond the artistic boundaries of painting.

His early work from the late 1950s, now part of the family and MoMA collections, are lyrical explorations where calligraphic script as a symbolic element is related to the tachiste understanding of colour. In 1959, he began to use Eastern images in his paintings, whereas in the 1960s, abstract and figurative elements began to stand out. This interaction in his paintings brought together themes of social memory and cultural heritage. His paintings were also influenced by existential philosophy, and he uses religion and sexuality not as opposing elements, but as metaphors surrounding the individual.

From 1950 to 1960, he continued to search for his own unique language of narration within the diversity of the organic abstract. In addition to the small-scale post-cubist paintings he produced in an academic style in the early 1950s, he also sought a synthesis that would emerge from his interest in the Islamic tradition, Sufism and Eastern arts. Abstract and figurative elements were emphasized in his works from the 1960s. He uses architectural images throughout his career. For Erol Akyavaş, architecture is more than a physical space; it is the representation of the vital and cultural production field of existence.

“The Glory of the Kings” (1959) is his first work to be included in the permanent collection of an international museum. In 1961, with this work, he became the first Turkish artist to be included in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, when he was only 29 years old.

The labyrinth had a continuing attraction for Erol Akyavaş since his childhood. To seek what lies beyond appearances, and to enter into a field of ambiguity, helped his inner world develop. In the first half of the 60s he used the female body as an aesthetic element, and from the 80s on, he began to use text in his paintings. In the late 1970s, labyrinthine geometric surfaces with a metaphysical influence appear in his paintings. The labyrinth, both as a concept and a form, occupies a special place in the artist’s work, and diversifies within itself. The labyrinths of the early 1970s are curved, and are shaped as introverted architectural lines. In the 1980s, Akyavaş mostly revised works from previous years in new compositions. He brought together the bird’s-eye-view landscapes, brick buildings, fortresses and labyrinthine forms of the 1970s and the amorphous figures of the 1960s in a more detailed, abstract style. During this period, Akyavaş appropriates the art of photography which he previously used in the 1960s for a more pictorial narrative.

In works that focus on grand historical narratives such as “The Alchemy of Happiness”, “Mansur Al-Hallaj”, and “Mi’raj Nameh”, he employs the art of Islamic calligraphy, and especially the letter Vav, and charts and symbols with universal meaning taken from ancient religious books. He combines the West and the East with his unique architectural, pictorial and imaginary elements. Concepts, treated periodically in his paintings, are in constant movement and transformation. In the 1990s, the symbolism in his paintings, puts forward with a lyrical narrative the position and uniqueness of the individual in the spatial context, and relates the problem of existence with placeless and timeless images that have attained abstract spirituality.

Press Conference

The press conference held on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition was attended by Erol Akyavaş’s wife Ilona Akyavaş, Istanbul Modern Chair of the Board Oya Eczacıbaşı, Finansbank Executive VP in charge of Private Banking Tunç Erdal, Istanbul Modern Chef Curator and exhibition curator Levent Çalıkoğlu.

Istanbul Modern Chair of the Board Oya Eczacıbaşı spoke of how Erol Akyavaş, by combining the mystical and sufistic aspect of Eastern art with Western art’s search for abstraction, sought what lies beyond the mere appearance of reality: “Having explored Sufism with endless curiosity since his childhood with the “excitement of perhaps capturing something from within”, Akyavaş reflected his world-view, beliefs and aesthetics through his use of traditional symbols and images and, applying the delicate and detailed technique of master jewellers, created new forms that make historical references to cultural heritage, versatility, emotions, intuition and dreams. Akyavaş produced multidirectional work nourished by architecture and photography, remaining distant to movements of the time, and subsequently he became inspired by religious and historical stories. In his work from this period, he re-fictionalized historical imagery to make it relevant, this way moving the past into the present. By focusing on dualities such as past and future, clarity and obscurity, eternity and mortality, consciousness and intent – Akyavaş aimed to re-produce the crucial values of tradition.”

Oya Eczacıbaşı added that they were pleased to realize an exhibition that presented Erol Akyavaş’s exciting adventure of over 40 years, who took on the challenge of possessing both Eastern and Western values, created a unique synthesis between his own tradition, Islamic art and culture, and Western art, culture and thought: “Organized under the patronage of Ilona Akyavaş and family, this exhibition has a special place among the retrospectives we have held thus far. I would like to take this opportunity, therefore, to express my deepest appreciation to Ilona Akyavaş for her invaluable support and attention to detail during the preparation of the exhibition. I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to Finansbank for helping to make this exhibition possible.”

"A country's development is not solely based on economic growth, it draws force from humanitarian values such as art, culture and sports" said Tunç Erdal, Finansbank Executive VP in charge of Private Banking, in his address during the press conference. Erdal further said: "In this regard, Finansbank has been committed to support art and creators of art since its foundation. We have prepared a retrospective book on Erol Akyavaş as a gift to admirers of art in our 20th anniversary. And today, we are delighted, as much as honored,to support the retrospective exhibition of this great master, who reflected eastern and western cultures to his art, with a unique artistic language and a distinctive focus on human nature. We are honored that 'Fihi Ma Fih', a creation of the master that belongs to our bank's art collection will take part in this exceptional exhibition."

Istanbul Modern Chef Curator and exhibition curator Levent Çalıkoğlu stated that Erol Akyavaş was an artist who lived with his dreams, fears, sexuality and faith, and revealed that it was himself that was in actual fact at the centre of his art, adding, “Despite all its visual, symbolic, divine and expressionist references, Akyavaş’s art represents the loves, experiences, joys, fears, weaknesses, affections and friendships their producer has experienced throughout the period of time he continued to breathe. He visualizes the journey traversed to become human, the mysteries of the world that comes before and after, and the labour we exert to breathe.”

Levent Çalıkoğlu further emphasized that Erol Akyavaş composed a deep and diverse visual world that passed through a wealthy tradition of narrative and belief, and that at the centre of this ‘search for the other world’ which set him apart from his contemporaries, lied an existential love, an infinite curiosity towards the unknown and the desire to transform into art the divine which he felt he belonged to. Çalıkoğlu stated that Erol Akyavaş had, with great relish and excitement, accepted “a new world” as his field of work, which he believed had so far been kept outside of the art of painting: “The main axis of this synthesis is to abandon the method of thinking based on the boundaries of painting in the Western sense, and to settle accounts with the hitherto unvisualized knowledge and culture of the East. With unequalled visual creativity, he invites to his art the world and perspectival perception of the East that expresses itself on the surfaces of the art of miniature, the complex bond between the human being and God, the rich narratives of tales of heroic adventures that are at times poetic and melancholic, and at other times provoke the imagination, and the dark rectangular of the holy Kaaba.”

PERIODS

Introduction / The 1950s

Erol Akyavaş was born in 1932 in Istanbul. He studied painting as a guest student at the Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu studio at the Fine Arts Academy, and took part in the exhibitions of this studio. In 1954, he travelled to the United States of America to study aesthetics and art philosophy. There, he studied architecture with Mies van der Rohe, a leading architect of the period. He also worked as a photographer for a period of time; however, neither photography nor architecture provided Akyavaş with the artistic satisfaction he sought. He returned to painting and until his death in 1999, he produced countless images, and meanings with a style, which went beyond the artistic boundaries of painting.

Immediately after graduating from high school, he built his painterly style in the early 1950s with an attitude that sought its source in both the East and the West. His paintings from 1952 display a post-cubist tendency, and contemporary explorations of the art of painting in the West. An interest in Islamic and Eastern art, a pursuit that would develop throughout his life, is clearly visible in his lithographies. The composition and search for meaning in the prints he produced in the 1950s in reference to the poetry of the sufi Yunus Emre, were harbingers of the calligraphy-influenced applications, figurative abstractions and the effort to perceive the surface of the painting as a whole divided into parts, that would appear in later years. Once he abandoned architecture and returned to painting, the lines in his works resembled stains that disappeared in the surface of the painting. He begins with a black background, illuminates the canvas by adding light-coloured layers of paint, and forms his paintings by masking the layer beneath. The forms are lightened, and they become softer and curved. Circular and spherical lines, the inherent characteristic of Eastern aesthetics, are combined with the human figure and limbs.

1960s

In the 60s, Akyavaş included various animal bones and seashells onto the canvas surface in his search for a wealth of meaning and form. He strives to extend the boundaries of the art of painting not only with a diversity of form but also materials. These objects are replaced in time by human figures. Works produced in the mid-1960s such as “Women”, “Rooms” and “Brothel” reflect the effort to depict the human body and world in its most ordinary state. In his series titled “Memories” his interest in the mysterious and invisible aspect of life is revealed. These paintings are random compositions displaying the influence of surrealism, and featuring traces of narratives and images drawn from the subconscious. Akyavaş attempts to reveal the unseen aspect of the human mind. By inviting the past into the present, he recalls memory. The works he produced in Göreme, where he was posted in 1963 for his military service, expand the boundaries of his landscape painting style and form examples of Akyavaş’s abstractionist approach.

1970s

The “Icons” series he began in the 1970s perpetuates the symbolic and representational tradition Akyavaş began to explore via sexuality in the 1960s. The surface of the painting once again features the collage technique he used in the 1960s. Compositions he has formed with faces, objects and forms assembled from different sources have been affixed to the surface of the canvas. Countless beads and stones in various colours and sizes that cover the entire surface exemplify the ornamental style Akyavaş began to use in the 1970s. The fortress, shelter, and city wall images and architectural city plans that would feature widely in the 1980s appear for the first time in the “Friendly Cities” series. Paintings that feature collages made of pieces such as bullets and mounted troops are reminiscent of images from an urban uprising.

The human body, which was depicted as an amorphous figure in the 1960s, became an abstract, simply delineated form in the 1970s. Labyrinthine forms appear in the artist’s work during this period. In the early 1970s, the outlines of the labyrinths are curved, however, towards the late 1970s these lines take on a sharper and more geometrical form. Akyavaş creates puzzling games of perception using the effect of shadows and light on the surface of the painting, and he presents new, bird’s-eye-view perspectives. In the “Heads Series”, featuring intense pattern drawings, repeated lines create figures, and solitary, severed heads reminiscent of heads of creatures and demons. Controlled by hooks and ropes attached to their faces, they form the narrators of stories that are difficult to understand.

1980s

From 1981 on, Akyavaş created a photography-based series on the Cologne Cathedral. These are amorphous, undefined narratives that emerge via interventions on photographs. The fine craftsmanship in these works is reminiscent of the curving lines of the labyrinths that appeared in the artist’s work in the mid-1970s and the “Heads Series” from the late 1970s. These are imaginary landscapes formed of the amorphous figure, abstract drawing and the photograph of the cathedral that often appears on the periphery of the painterly field.

The title of the series “De Mortuis Nil Nisi Bonum” means “it is inappropriate to speak ill of the dead” in Latin. The most significant images in these works are canine heads chained by the neck, and severed human digits. These paintings feature traces of previous works such as the Fortresses series and the bird’s-eye-view landscapes. In the “Time Erases Everything” series that commenced in 1981, x-ray images are added to the severed arms and fingers. A new dimension is added to the human body with the layer visible in the x-ray. Akyavaş produced his largest canvasses in 1982. These works are composed of great fortresses and city walls built with bricks and depicted from a bird’s-eye perspective. The works featuring severed fingers, ears and teeth made of plaster and affixed to the canvas surface are reminiscent of the relationship between history and death.

The Mansur Al-Hallaj series, which began in 1987, takes its name from the mystical author and poet Mansur Al-Hallaj who followed the sufi way of life. Images from Tawasin, the book Al-Hallaj wrote after he was imprisoned for proclaiming “Ana l-Haqq”, appear here for the first time in Akyavaş’s painting. He creates a new form and pattern of meaning using calligraphic forms and signs assembled from religious books. In the centre of the works in the series which was executed both on canvas and painting is the letter “Vav” that represents Allah. Since the 1970s, masses of colour accompany the old script, and religious symbols in Akyavaş’s paintings. These are presented in basic forms such as the circle, the square or the rectangular. The empty spaces in the painterly field are much more dominant compared to previous work. Beginning with the “Kaaba” series he first started to work on in 1989, Akyavaş returned to abstract painting. The “Firman” series he worked on during the same period, brought together images from miniatures and religious books that were made into collages. Akyavaş inscribed various signs into these works. The technique of inscription [scraping/etching] would appear on the surface of many works in the 1990s. For the print series he realized in 1987, Akyavaş chose the “Mi’raj” as his subject matter. Mi’raj, meaning ascension, is interpreted as the ascension of the Prophet Mohammad to heaven. Akyavaş visualizes this story on eight different surfaces in different compositions.

1980s

Akyavaş’s three-dimensional work dated 1989 and titled “Fihi Ma Fih” alludes to the history of the Hagia Irene church. The symbols the artist has inscribed on Plexiglas plates represent the three monotheistic religions. By bringing together these symbols in a single space, Akyavaş points towards religious and cultural unity and togetherness. As for the 4th tablet that stands opposite to these three tablets, the calligraphic rendering of the name of Allah reminds the viewer of reaching the true essence by dissolving one’s self in the existence of God as in the sufi tradition, and attaining divine truth through the love of God

1990s

In the 90s, Erol Akyavaş produced works by etching broad surfaces. During these years, he brought together and reinterpreted all the images and signs he had until then conveyed to the surface of the painting. In the 1990s, we see him divide the surface of the painting into sections, and embed beneath the paint smeared on the canvas images of miniatures and those assembled from religious books. The absolute masses of colour he uses are reminiscent of his works from the early 1950s. There is a plain use of image, line and colour. Akyavaş further developed his reductionist abstract style in the 1990s.

In certain works from the 1990s, we see Akyavaş sustain his figurative approach to painting. In a lithography series dated 1993, the iconic figures produced by using sedimented paint on paper which is reminiscent of residual fragments of earth, are accompanied by pages from books, and collages made of miniature paintings. Returning to these works after the printing process, Akyavaş created narratives on the surface with complex text and visuals. Two different prints about the Bosnian War are exceptions to works composed around iconic figures. This time, Akyavaş turns a female body, depicted as a victim of war, into an icon, and places only this figure at the centre of the composition. He does not change the composition by intervening either with text or sign, and draws attention to the catastrophic aspect of humanity via a contemporary account of destruction.